Watford City, North Dakota

One thing I have always valued about my work is the adventures it takes me on – the people and places I learn from along the way. The thing about adventures, similar to artmaking, is what makes it an adventure is that there is a leap involved, a risk. Leaps, risk: not always easy. It is only in the rearview mirror, when I see the ways I was stretched that even my sideways adventures seem worth the ride.

Painting in North Dakota seemed like a good idea when I first considered it, from the safety of my couch at home. Having my artwork at a museum would be a great venue for my work, a career milestone. I had already completed one project with LeRoy Lillibridge successfully. North Dakota, well, that’s someplace that would have never crossed my mind to visit if a project had not called me there, but limiting my options to what I think would be the nicest destination for my tastes would be a very boring life!

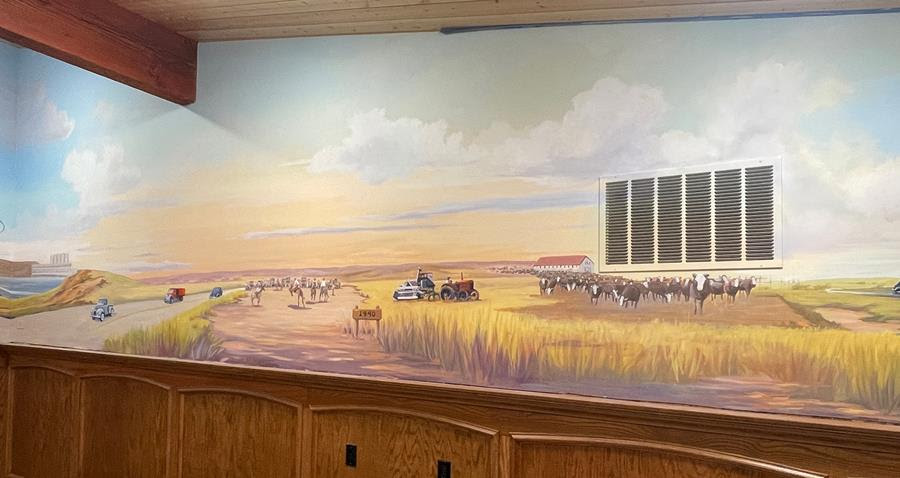

I certainly had reservations. Many. The project would require a higher level of detail than any previous mural I had painted. The subject- the history of Watford City, ND- which is also the history of cattle ranching, oil extraction, and the leap from homestead to industrial-scale farming, was something I knew nothing about. I was quite comfortable painting buffalo, elk, trappers, and trees, but by 1900 there were no more elk, buffalo, trappers, or trees in Watford City. I would have a very short comfort zone and a very long journey of learning their history with a wide-open lens, to tell a story that was not mine, but would come through my efforts to paint everything in the most beautiful light I know how. Amid my hesitations, LeRoy suggested that I could come whenever I wanted, whatever was the least busy time of year for me. That is how I decided that I could certainly make time in my schedule in February for the project…

Winter in Watford City, 1900. Mail delivery to this small farming outpost was a big deal all year-round.

When I look back on my early proposals, to paint the mural on canvas in the comfort of my home studio, and just make a quick trip out to install it, or at a minimum complete the designs before I head out to paint, my naiveté makes me smile. LeRoy is a third-generation North Dakotan. He has started three businesses that boomed and busted along with the shifts in the economy. He has a passion for history and has deep roots in the community, in ranching culture, and in oil culture. Despite his passion for the project, LeRoy communicates with the minimum number of syllables possible. He’s not pushy with his ideas, (I am a veritable spigot, it can be overwhelming), and agreements are made with eye contact, not through text messages. LeRoy is also willing to wait, patiently, sometimes weeks, for the light of understanding to dawn upon the suburban California woman who’s never had more than light splashes of paint on her work boots. Every time I sent a new round of Google-researched designs to Leroy, he would respond, “Well, I think you just need to come out here and we can talk about this together.”

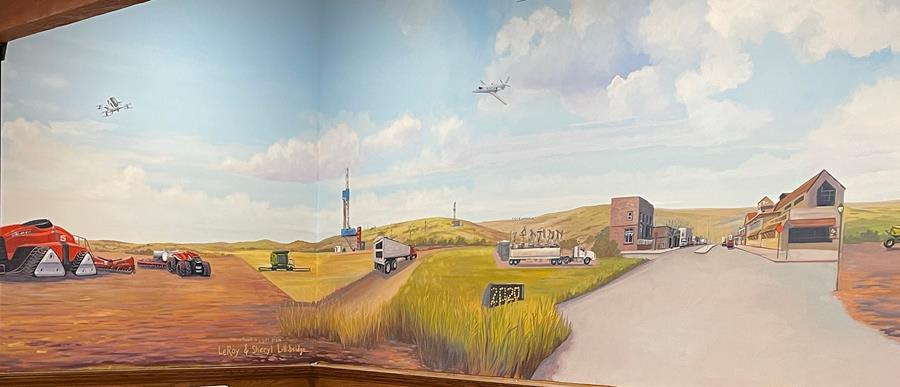

The first trip I took out in February was slow going. Also cold, but I was expecting that. LeRoy and I spent two weeks in the media room together hashing out what goes where, the basics of three-point perspective, and the finer points of haying and combines. At times, it was a competition of wills, but every afternoon LeRoy popped me fresh popcorn from the museum popcorn machine and I would realize we had, indeed made some headway that day. LeRoy was a local farm boy who had retained the mineral rights on his and his wife’s generational homesteads, something the majority of locals had sold along the way. He was making money from the oil extracted under his grandparent’s land, and this mural was a gift from him and his wife, Sheryl, back to the community. LeRoy has spent every day except Sunday on site for the last seven years of his life overseeing the building, procuring, and curating this museum that celebrates the history of McKenzie County, which is currently the largest oil-producing county in the United States. (Another fun fact: there are more cattle than humans in North Dakota.) He cares deeply about this project and felt strongly that I was the right artist to carry out his vision. I know this because I tried to quit the project twice, and he wouldn’t have it.

On my first trip out, we managed to block out the design on four walls around the media room, which will double as a community gathering space. The room was beautifully detailed with oak paneling, all cut and installed by LeRoy himself. I used a projector for all the man-made elements, to make sure all the proportions were correct. We had an endearing process where I would give him a deadline: LeRoy, you have to get me the image of the exact 1957 Chevy you want by this afternoon, otherwise I am going to pick it out myself. (If he missed his deadline, I would inevitably pick a rag top instead of a hard top, or it would be the wrong rims, etc.) Leroy would find me the image and hand his phone to me up on the lift, I would airdrop the images to myself, and pop them into the projector and say Here? Bigger? A little to the right? Sometimes I would paint the image he provided and then he would say, later, something like, “There is a grain filter on that harvester, and nobody ever used grain filters, so you can just paint that out.” Could you identify an ancillary grain filter on a vintage harvester? Another time: Those shocks should be thicker at the base. Shocks. Shocks…is that something on that thingamajiggy I painted? No, shocks are bundles of wheat tied together in the field. Ahhha. The bundles of wheat. LeRoy never lost his cool with me or used any extra syllables to explain what he wanted. At some point, I would come to understand that each of these details mattered. Details that looked fine to my eye would have stood out as wrong to every North Dakotan that walked in there. For example, I didn’t understand why the grain truck had to be right next to the field when it would be more aesthetically pleasing if it was in another area, like by town, but the fact that the new combines ( they cut and separate the wheat from the chaff in one machine, a combination of tasks, thus, the name) have a chute out the side so they can just fill up the grain trucks right in the field, is an important innovation for large-scale farming. Betcha didn’t know that!

We included the outline of Lake Sakakawea, and indicated the location of the Garrison Dam. At over 2 miles in length, the dam is the fifth-largest earthen dam in the world.

After we blocked in the skeleton of the content, I went home to rest up for round two. LeRoy has been dependent on a pacemaker for about five years, and he went in for heart surgery which delayed my second trip. I flew back out in mid-April to finish up the project.

This photo is from April 20, a late spring snowstorm which followed a three-day windstorm. While my friends sent me their sunny photos from “super bloom” hikes in California, I was putting scoops of spirulina in my oatmeal to supplement my hamburger-centric diet. FOX News was on in the breakfast room at the hotel every morning, and I never miss breakfast, so I was also digesting Fox News on the daily. I came to understand how people who watch Fox News can come to Fox News conclusions. They are very good at producing alarm bells in listeners through careful word choice, from likable, cheerful commentators who might live next door and seem genuinely concerned for our country. I experienced cognitive dissonance as there was almost no overlap in content with the news I get from the New York Times. I kept my conversations to the weather and got along with everyone I met just fine.

I went out to dinner (what we call lunch) with LeRoy and his team and we all ordered the special: Hot Hamburger. Hot hamburger is a beef patty between two slices of Wonderbread and a scoop of mashed potatoes, covered in gravy. Vegetables are definitely ancillary in North Dakota. When I asked if they had a salad, the waitress responded “Oh yes! We have an excellent macaroni salad. I realized on the trip how spoiled I am by being close to the fruit and vegetable bounty grown within hours of my house. My supper (dinner) every night was a second bowl of oatmeal with a scoop of spirulina. Oddly, that meal will probably always remind me of North Dakota, even though nobody there would eat that!

On the last wall we included new technology: drones and prototype tractors controlled by AI.

On my last day, in our final parting, Leroy and I shared several hugs, meaningful and mutual. We had taken this adventure, this unlikely collaboration, and dreamed this beautiful work of art into existence together. It was a beautiful legacy we had created for the community. “Sorry I’m not so easy to work with,” said LeRoy. “Sorry for my sharp edges,” I said. Together, we laughed at ourselves.

Thank you for reading along with the latest chapter in my art adventure. I hope you are feeling as grateful for the warmth of spring that has finally arrived as I am.

With love,